The Baseball Hall of Fame remains perhaps the most venerated sports institution in the United States, filled not only with the greatest players in the sport’s long history, but also with virulent racists, noted cheaters, drug users, and your everyday run-of-the-mill sociopaths. The process and guidelines for selecting which former players deserve induction into the Hall of Fame are notoriously ambiguous and contentious, leading each year to hilariously exhaustive exegeses or truly bizarre ruminations on the meaning of the word “fame” in “Hall of Fame.” For some writers, though, the real problem with the induction process has less to do with the vague guidelines than with the fact that each player remains eligible for fifteen years; for such writers, it should be immediately obvious whether someone is a Hall of Famer or not.

While having to debate the merits of Jim Morris or Tim Raines (no and yes, by the way) every year is no doubt frustrating, there’s a certain historiographical wisdom to this system that is too often overlooked as voters must constantly review and rethink baseball history in light of new knowledge. This was perhaps best demonstrated earlier this month with the selection of Bert Blyleven, a former pitcher whose reputation has grown substantially over the course of the past ten years as advanced statistical analyses (known as “Sabermetrics”) have become increasingly accepted within the notoriously stodgy baseball community.

|

| Bert Blyleven: Hey, "taste" isn't a criterion. |

In his second year of eligibility, Blyleven captured just 14-percent of the vote (75% is necessary for induction) and was widely understood as a solid pitcher with a long career that was nonetheless distinctly unworthy of the Hall of Fame. Sabermetrics have, however, over the course of the past decade, revealed Blyleven to have been one of the greatest pitchers of his generation, chronically underrated, both while he was playing and in the present, because he was consistently saddled with terrible teams that masked his dominance. As a result, beneath the dry numbers in his voting record lies a fascinating shift in the way baseball history is understood and interpreted:

1998: 17.5 % 2002: 26.3% 2006: 53.3% 2010: 79.7%

1999: 14.1% 2003: 29.2% 2007: 47.7%

2000: 17.4% 2004: 35.4% 2008: 61.9%

2001: 23.5% 2005: 40.9% 2009: 62.7 %

At the conclusion of his career, most would have understood Blyleven to have been obviously unworthy of the Hall of Fame. In the intervening period, neither the facts about his career nor his statistical accomplishments changed. Yet the way we understand and periodize baseball has shifted so dramatically that he now seems an obvious Hall of Famer.

The wisdom of this system, I suspect, will be demonstrated even more fully in the next fifteen years as more and more players tainted with proven or unproven associations to steroids become eligible for induction. This year, for instance, at least four candidates’ cases likely suffered because of their alleged ties to steroids:

Jeff Bagwell 41.7%

Larry Walker 20.3%

Mark McGwire 19.8%

Rafael Palmeiro 11%

Had the steroid scandals of the previous decade never occurred, each of these players likely would eventually enter the Hall of Fame, but now their cases seem in increasing doubt. Bagwell, in particular, probably would have gained entry this year as one of the greatest first basemen in history. But even though there is no concrete evidence linking him to steroids, Bagwell’s skill-set as a home run hitter, his hulking body, and the time period within which he played was enough for a substantial number of writers—posing as moral guardians of a sacred institution—to conclude that he might have used steroids and could therefore tarnish the Hall of Fame. Rob Neyer points out that, by 2015, there could be as many as 22 entirely deserving candidates who played during the “steroid era” up for election and therefore could be considered suspect.

At some point, I think, we will really have to question: what was the “steroid era” anyway, how does it differ from what preceded it, and how does it fit into the broader history of baseball?

The most common interpretation is helpfully illustrated here, which understands steroids to have been introduced into baseball in 1988 by outfielder Jose Canseco, spread like wildfire while home runs flew out of the park at a record pace, and finally exploded into public consciousness with the BALCO case, becoming the single greatest embarrassment in the sport’s history since the Black Sox Scandal (and that whole segregation thing) .

Canseco is a reviled, bumbling, and bankrupt former star who was recently beaten into a whimpering fetal position in a schadenfreude-laden boxing match and, as such, makes for a convenient scapegoat. But, I think, there is good reason to be skeptical of this interpretation. Baseball, particularly if Ken Burns is to be believed, has always been approached as a representation of American identity and, as a result, the narrative of a "Steroid Era" draws upon--and feeds into--a popular narrative of national purity and innocence corrupted by modern excess--where have you gone Joe DiMaggio? But, of course, neither baseball nor America was ever as pure and simple as people like to believe.

The first known use of performance-enhancing drugs in baseball was not by Canseco, but instead by Hall of Fame pitcher “Pud” Galvin who used the “elixir of Brown-Sequard"--made by draining a monkey’s balls--to improve his performance, a decision which yielded accolades from the Washington Post: “If there still be doubting Thomases who concede no virtue of the elixir, they are respectfully referred to Galvin’s record… It is the best proof yet furnished of the value of the discovery.”

More seriously, though, performance-enhancing drugs were widespread in baseball by at least the 1950s, particularly in the form of amphetamines. Pitcher Jim Brosnan first revealed the widespread use of amphetamines by baseball players in his 1959 memoir, recounting how players believed it gave them a physical and emotional boost during the grueling baseball season. And boy howdy were amphetamines popular, used by everyone from Hank Aaron to Willie Mays (who was reputed to have kept a bottle of “red juice”—a mix of speed and fruit juice—in his locker).

But it wasn’t just amphetamines—players were dabbling with nearly any drug or cocktail they believed could give them a leg up on the competition or quell their physical pain. Hall of Fame pitcher Whitey Ford, for instance, was alleged by one teammate to use dimethylsulfoxide to fight is aches and pains: “you rub it on with a plastic glove and as soon as it gets on your arm you can taste it in your mouth. It’s not available anymore though. Word is it can blind you.” And by 1970s, of course, everyone was on cocaine and Dock Ellis was (hilariously) throwing no-hitters while tripping balls on acid:

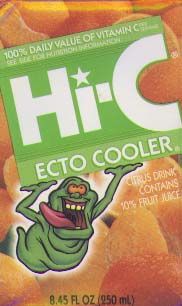

If amphetamines were widely believed (even if such a belief was false) to improve player performance in terms of reaction and hand-eye coordination, it’s worth asking what precisely the ethical distinction between Barry Bonds using anabolic steroids and Willie Mays using Hi-C from hell is.

|

| This was my performance-enhancer back in my T-ball days. Laced with speed, of course. |

Steroids were also known to be widely used in nearly every other sport throughout the 1960s. In 1969, a lawsuit by a former defensive lineman revealed that the San Diego Chargers gave their players—and sometimes forced their players to take—anabolic steroids and amphetamines in an attempt to enhance their performance. Indeed, steroids were casually placed on the training table along with amphetamines, pain killers, and sleeping pills. The use of steroids was so prevalent that, by the summer of 1973, both the Subcommittee on Investigations and the Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency held hearings to determine the extent of drug use within American athletics.

|

| Actually not about this year's Vikings team. |

But not everyone was satisfied with this assessment.When Senator Birch Bayh tried to get Jack Scott, the founder of the Institute for the Study of Sports in Society, to praise baseball's anti-drug initiative,Scott adamantly refused. Instead, he suggested such anti-drug programs were merely a coverup that fixated on drugs like heroin and LSD instead of those that were actually in widespread use by athletes: “Here, for example, is a book that is put out by the office of the Commissioner of Baseball. The “Baseball vs. Drugs” and this is an education prevention program. There is not one mention of anabolic steroids in the entire booklet—one of the chief drugs athletes are using to help their performance."

So by the 1950s and 1960s, American athletics were saturated with a culture of drugs, which were widely available; admitted users have suggested they were in widespread use; baseball players were widely accepted to be using amphetamines and other newfangled elixirs to gain an edge. Is it really a stretch to believe some of the greatest players of the 1960s and 1970s may have been using anabolic steroids in addition to amphetamines? Would it even be possible that steroid use has declined overall since the 1960s, but merely become more effective? Lastly, what precisely is the ethical distinction between using drugs one thinks will yield performance-enhancement and using drugs that actually yield such enhancement?

I suspect such questions will be asked in upcoming years, as more and more people delve begin to challenge the romantic narratives of baseball's simple past. How will it change the way we think about baseball history over the past 20 years? It will be interesting to see if, and how, our analysis of the last thirty years begins to change.

4 Response to Good Question: When Did Baseball’s Steroid Era Begin?

Holy cow, I thought that Pud Galvin and goat testicles was where the post was going to drive off the cliff into fiction--you know, making stuff up to achieve some greater truth--but no, this is all real, you have links.

You know what I want? I want more folks from the '60s to say they roided. Not speed, but full-on anabolic steroids. There were hundreds and hundreds of players, many of them washouts with nothing to lose by talking now, and if I'm going to believe that most pitchers on every team were putting steroids in their body (the reason, with the high mounds and big parks, for the era of pitching?) I need more than one or two half-hearted whistleblowers.

Yeah, I agree Dave that there's some reason for skepticism and that you would have expected more than just a few people to have come forward if it was as widespread as some people claim. But, at the very least, there does seem to be enough anecdotal evidence (a lot of which, as best as I can tell, no one has sifted through for forty years) that suggests that *some* players probably were 'roided up. And it wouldn't be at all shocking if some of the all-time greats from the late 60s and early 70s were included.

I am really impressed by the detailed and rich information about the era of baseball steroids. In reference to the matter preferring to discuss few more initial words about steroids which i believe will enrich the subject matter.

Drugs unremarkably said as Steroids are classified as anabolic and cortico steroids. Cortico steroids, like adrenal cortical steroid, square measure medicine that doctors usually inflict to assist management inflammation within the body. They are usually accustomed facilitate management conditions like respiratory disease and lupus. They are not the same because the anabolic steroids that receive most media attention for his or her use by some athletes and bodybuilders.

Anabolic steroids square measure artificial hormones which will boost the body ability to supply muscle and forestall muscle breakdown. Some athletes take steroids within the hopes that they are going to improve their ability to run quicker, hit farther, carry heavier weights, jump higher, or have a lot of endurance.

Anabolic steroids square measure medicines that match the chemical structure of the body’s natural internal secretion androgen, which is formed naturally by the body. Androgen directs the body to supply or enhance male characteristics like accrued muscle mass, facial hair growth, and deepening of the voice, and is a vital a part of male development throughout pubescence.

When anabolic steroids increase the amount of androgen within the blood, they stimulate muscle tissue within the body to grow larger and stronger. However, the result of an excessive amount of androgen current within the body is harmful over time.

Steriod can really be a good help if not abused

Buy Steroids Canada

Post a Comment